[ad_1]

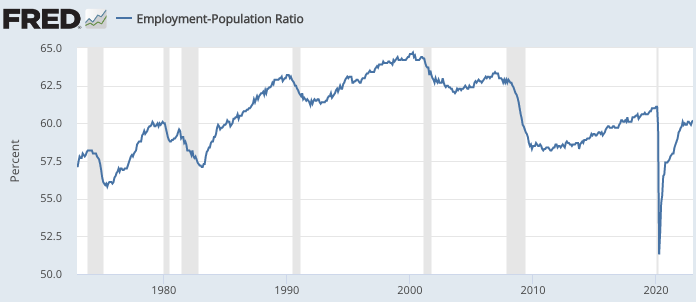

When confronted with proof that the job market is crimson sizzling, naysayers usually level to the employment-population ratio (E/P), which stays beneath pre-Covid ranges:

How can this be? In spite of everything, the US whole inhabitants has risen by lower than 1% over the previous three years. In distinction, payroll employment is up by 2%. Shouldn’t the employment/inhabitants ratio now be about 1% above pre-Covid ranges?

I discovered two explanations for this discrepancy. First, the E/P ratio is calculated utilizing the family survey of employment, which is up by just one% over the previous three years. The family survey is broadly considered as being much less correct than the payroll survey, however I don’t have large drawback with its use right here. Even a 1% rise in whole employment barely exceeds the speed of inhabitants development. So why is the E/P ratio decrease than pre-Covid?

It seems that the E/P ratio is calculated by dividing family survey employment by not the full inhabitants, fairly by the non-institutionalized inhabitants age 16 and over. That appears cheap, so what’s the issue?

It seems that the BLS has a really bizarre estimate of the over-16 non-institutionalized inhabitants. They declare it rose by 2.5%, from 259.502 million to 265.962 million over the previous three years. In distinction, the BEA says that the full inhabitants rose by 0.9%%, from 331.345 million to 334.420 million (which is what mainly what the Census Bureau says.) By implication, the comparatively small variety of youngsters and institutionalized will need to have plunged by 3.4 million, or practically 5%. That appears implausible for such a short while. (I couldn’t discover exact knowledge, however it seems just like the variety of American youngsters declined by about 1.6 million over the previous three years, and the institutionalized inhabitants is sort of small.)

I think that the BLS estimates of whole inhabitants over age 16 didn’t account for the sharp slowdown in grownup inhabitants development because of Covid deaths and a dramatic fall in immigration. And I additionally suspect that payroll employment is extra correct than the family survey. Put the 2 collectively, and it’s cheap to imagine that employment has now exceeded the pre-Covid peak of early 2020, even accounting for inhabitants development. That is particularly the case when one considers that the aged inhabitants is the quickest rising a part of the full US inhabitants, as child boomers like me retire in giant numbers. There isn’t a “hidden unemployment”.

Implications:

1. We’re booming; there was no recession in 2022.

2. When robust employment development is mixed with fast nominal wage features, there’s no proof for the declare that the Fed adopted a decent cash coverage in 2022. It didn’t occur. At greatest, they adopted a barely much less expansionary coverage than in late 2021. But when a driver slows down from 120 to 110 mph, would you describing his driving coverage as “sluggish”? So why describe financial coverage as “tight”?

3. Economists shouldn’t be within the enterprise of predicting enterprise cycles. We’ve by no means been in a position to do it, and it simply makes us look silly. We seem like a bunch of astrologers.

[ad_2]